The Phantom Tollbooth: The Book that Started it All

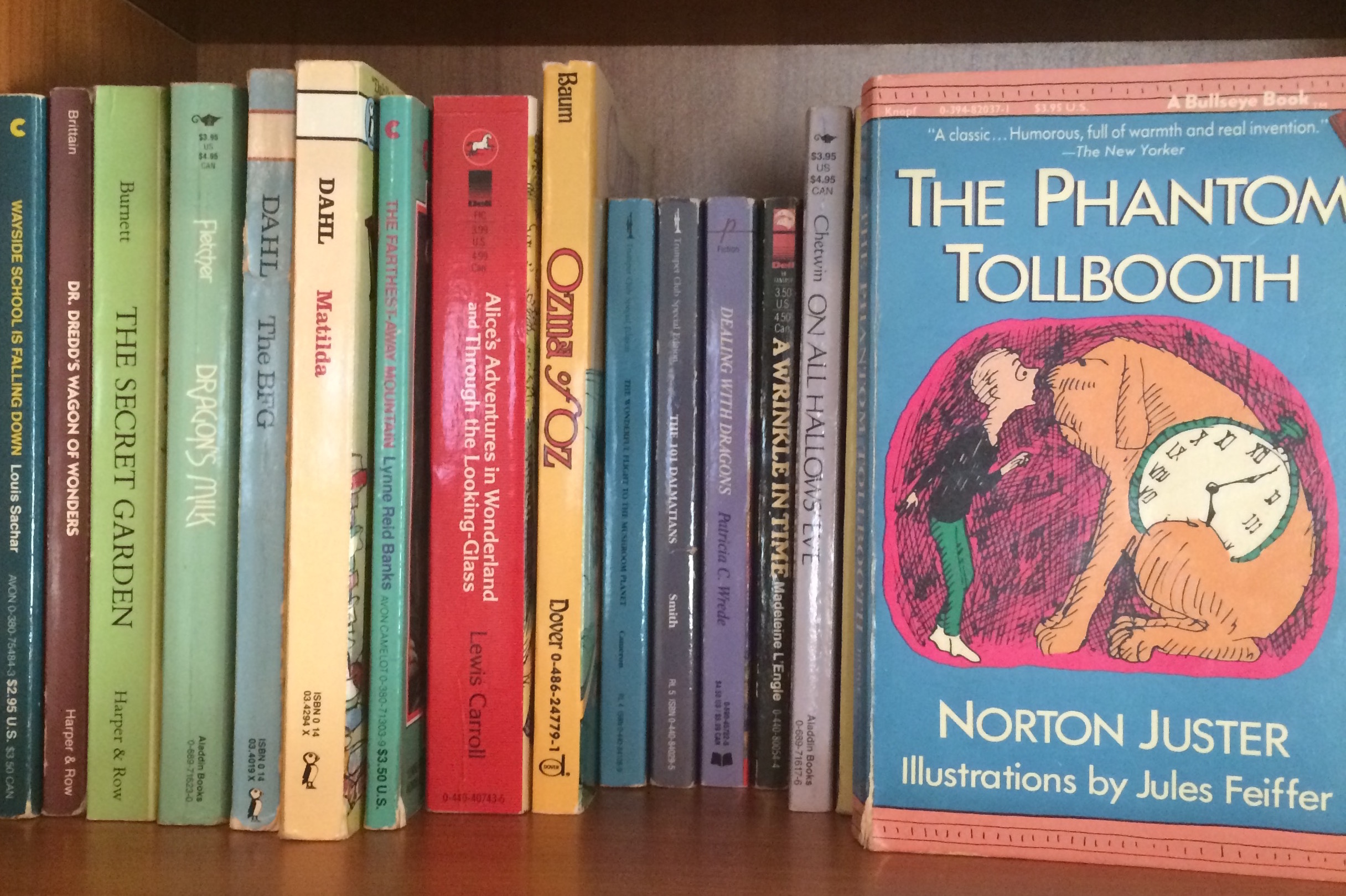

I was reflecting on my bookshelf the other night, a little Zen moment in the midst of an over-tired preschooler and a colicky newborn (stereo-screaming = fun times!). Up near the top are the books that have followed me since childhood. They’re my own personal classics, and I’ve loved them enough to lug them around with me from house to house over the years. Their spines, arranged in a neat row like literary sentinels, are a rainbow of memories. But there is one in particular, a blue one with pink borders and clean capital letters, that has been my favorite almost since I could read.

The Phantom Tollbooth.

It’s really the book that started it all: my love of fantastical places, my obsession with words, my passion for reading. The sight of it stirs something deep in my memory, and I can recall for just a moment that particular wonder exclusive to children. It’s bittersweet, just an echo of a world that I can now only observe through my own daughters, but a beautiful one nonetheless.

I took it off the shelf. I hadn’t read it in years, but I felt like I needed to revisit its familiar pages, run my eyes and my mind over the words that had made such an impression on me growing up. I wondered if the story would still resonate with me, or if like many things that hold you rapt as a child, it wouldn’t stand the test of time.

I cannot remember exactly what drew me to it all those years ago. I suspect it was the way I related to the main character Milo’s all-encompassing boredom, a facet of childhood that I recall quite clearly, especially on endless summer days when time seemed interminable. I also have a hunch it was the wondrous adventure he undertakes and the cast of intriguing characters he meets along the way.

And then there’s the word play. Norton Juster, the book’s author, is a master of it, and I loved the way he made those funny expressions adults used literal and comical. There is a watchdog that actually has a watch for a body, and an island called Conclusions that one must jump to in order to visit.

But what I think I understood only superficially when I was younger, is that the book is really a meditation on the value of learning.

For those of you unfamiliar with The Phantom Tollbooth you would do your grown-up self a favor by reading it and your kids an even greater service by sharing it with them. In a nutshell, Milo is a boy troubled by a deep-seated ennui. He sees nothing interesting about his world. He is surrounded by toys and games but none of them engage him. He sees nothing valuable about school.

Then one day a mysterious gift arrives, a cardboard tollbooth that takes him to a remarkable land dominated by the city of Dictionopolis in the south and the city of Digitopolis in the north. In between are places like the Doldrums, the Forest of Sight and the Valley of Sound. As he sets out to explore this new world he becomes involved in a quest to rescue the lost princesses, Rhyme and Reason, who have been locked away in the Castle in the Air by their brothers the kings of Dictionopolis and Digitopolis. Since their incarceration the land has suffered, for while the people all know many things their knowledge means nothing without the guiding influence of Rhyme and Reason.

Unfortunately, the castle in the air is located high up in the Mountains of Ignorance where innumerable demons stand in Milo’s path. There’s The Horrible Hopping Hindsight, the Overbearing Know-it-all, the Gross Exaggeration, and the Gelatinous Giant who hates change and new ideas. My favorite is the Terrible Trivium, the demon of worthless tasks and wasted effort. Milo asks him why he should only want to do unimportant things. And he responds in a way that reminds me very much about my rant on not having time:

“If you only do the easy and useless jobs, you’ll never have to worry about the important ones which are so difficult. You just won’t have the time. For there’s always something to do to keep you from what you really should be doing.”

In the end all the demons of Ignorance attempt to foil Milo’s rescue plan, but are thwarted by the combined forces of the land of knowledge.

Admittedly the metaphor is not very subtle but the lesson is just as important now as it was then. Embrace learning, keep the evils of ignorance at bay, engage your senses, be open to new experiences, the world is an amazing place. Indeed, the book is chock full of truth bombs.

An example can be found in my favorite quote which comes when one of Milo’s sidekicks, the Humbug, is talking with the Mathemagician, the ruler of Digitopolis, about how he was able to multiply himself into seven distinct Mathemagicians using his magic staff (which looks suspiciously like a writing instrument):

“But it’s only a big pencil,” the Humbug objected tapping at it with his cane.

“True enough,” agreed the Mathemagician; “but once you learn to use it, there’s no end to what you can do with it.”

That idea, that the pencil is a mighty source of magic, is incredibly powerful.

Near the end of the book when Rhyme and Reason have been safely returned, Milo feels bad that it took him so long to rescue them, lamenting that the number of mistakes he made along the way added time to the trip. Reason reassures him with the following:

“You must never feel badly about making mistakes,” explained Reason quietly, “as long as you take the trouble to learn from them. For you often learn more by being wrong for the right reasons than you do by being right for the wrong reasons.”

Boom. Maybe I should just have Norton Juster write my posts from now on.

In the end when Milo returns to this world his eyes are opened to the many possibilities it holds.

“Outside the window, there was so much to see, and hear, and touch – walks to take, hills to climb, caterpillars to watch as they strolled through the garden. There were voices to hear and conversations to listen to in wonder, and the special smell of each day. And, in the very room in which he sat, there were books that could take you anywhere, and things to invent, and make, and build, and break, and all the puzzle and excitement of everything he didn’t know – music to play, songs to sing, and worlds to imagine and then someday make real.”

What book from your childhood inspired you?

- Categories:

- Reading

Thanks for a wonderful post. I am trying to translate the book into Norwegian, for it is practically unknown here.

Andreas